Optiscope is an experimental Lévy-optimal implementation of the pure lambda calculus enriched with native function calls, if-then-else expressions, & a fixed-point operator.

Being the first public implementation of Lambdascope 1 written in portable C99, it is also the first interaction net reducer capable of calling user-provided functions at native speed. This combination allows one to (1) embed all primitive types & operations through C FFI, (2) interleave lazy evaluation with direct side effects, and (3) let optimal reduction share calls to pure C functions just like ordinary β-reductions. As such, Optiscope can be understood as an optimal λ-calculus reducer extended to sharing foreign computation.

In what follows, we briefly explaine what it means for reduction to be Lévy-optimal, & then describe our results.

To every person to informe me of a semantic bug, I will pay $1000 in Bitcoin. More details here.

$ git clone https://github.com/etiamz/optiscope.git

$ cd optiscope

$ ./command/test.sh

See optiscope.h for the user interface & tests.c for the comprehensive usage examples with different data encodings.

The shell commands are outlined in the following table:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

./command/test.sh |

Execute the test suite tests.c. |

./command/example.sh <example-name> |

Execute the example examples/<example-name>.c. |

./command/graphviz-state.sh |

Visualize target/state.dot as target/state.dot.svg. |

./command/graphviz-all.sh |

Visualize all the .dot files in target/. |

./command/bench.sh |

Execute all the benchmarks in benchmarks/. |

Following the classical example (here borrowed from 2):

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. ((λf. (f (f (λz. z))))

(λw. (h (w (λy. y)))))))

This term conteyns two redexes: the outer redex ((λg. ...) (λh. ...)) & the inner redex ((λf. ...) (λw. ...)). If the outer redex is to be reduced first, which follows the normal order reduction strategy, the term will reduce in a single step to:

G := (λh. ((λf. (f (f (λz. z))))

(λw. (h (w (λy. y))))))

(G (G (λx. x)))

which will cause duplication of the inner redex ((λf. ...) (λw. ...)), thereby entailing duplication of work.

On the other hand, if we follow the applicative order strategy, then four instances of the redex (h (w (λy. y))) will need to be processed independently, againe entailing duplication of work:

Show the full reduction

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. ((λf. (f (f (λz. z))))

(λw. <(h (w (λy. y)))>))))

↓ [f/F]

F := (λw. <(h (w (λy. y)))>)

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. (F (F (λz. z)))))

↓ [(λz. z)/w]

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. (F <(h ((λz. z) (λy. y)))>)))

↓ [(λy. y)/z]

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. (F <(h (λy. y))>)))

↓ [<(h (λy. y))>/w]

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. <(h (<(h (λy. y))> (λy. y)))>))

↓ [g/G]

G := (λh. <(h (<(h (λy. y))> (λy. y)))>)

(G (G (λx. x)))

↓ [(λx. x)/h]

(G <((λx. x) (<((λx. x) (λy. y))> (λy. y)))>)

↓ [(λy. y)/x]

(G <((λx. x) (<(λy. y)> (λy. y)))>)

↓ [(λy. y)/y]

(G <((λx. x) <(λy. y)>)>)

↓ [(λy. y)/x]

(G <<(λy. y)>>)

↓ [<<(λy. y)>>/h]

<(<<(λy. y)>> (<(<<(λy. y)>> (λy. y))> (λy. y)))>

↓ [(λy. y)/y]

<(<<(λy. y)>> (<<<(λy. y)>>> (λy. y)))>

↓ [(λy. y)/y]

<(<<(λy. y)>> <<<(λy. y)>>>)>

↓ [<<<(λy. y)>>>/y]

<<<<<<(λy. y)>>>>>>

In this case, the cause of redundant work is the virtual redex (h (w (λy. y))): when w & h are instantiated with their respective values, we obtaine the same term ((λy. y) (λy. y)), which applicative order reduction is not able to detect.

A simpler example to illustrate the principle would be (taken from chapter 2 of 3):

once = (λv. v)

twice = (λw. (w w))

M = ((λx. x once) (λy. twice (y z)))

Proceeding with applicative order reduction:

((λx. x once) (λy. twice (y z)))

↓ [(y z)/w]

((λx. x once) (λy. (y z) (y z)))

↓ [(λy. (y z) (y z))/x]

((λy. (y z) (y z)) once)

↓ [once/y]

((once z) (once z))

↓ [z/v]

(z (once z))

↓ [z/v]

(z z)

Firstly, the (neutral) application (y z) is duplicated; however, later y is instantiated with once, which makes (y z) a redex. Thus, even if some application is not reducible at the moment, it may become reducible later on, so duplicating it would not be optimal. Ideally, both explicit & virtual redexes should be shared; applicative order shares onely explicit redexes, while normal order does not share any.

As also discussed in 2 & 3, the technique of graph reduction, sometimes termed lazy evaluation, is also not optimal: while it postpones copying the redex argument initially, it must copy a term participating in a redex, whenever the former happens to be shared. Consider the following term (adapted from section 2.1.1 of 3):

((λx. (x y) (x z)) (λw. ((λv. v) w)))

After the outermost reduction ((λx. ...) (λw. ...)) is complete, the two occurrences of (λw. ((λv. v) w)) are now shared through the same parameter x. However, as this shared part is participating in both ((λw. ((λv. v) w)) y) & ((λw. ((λv. v) w)) z) simultaneously, it must be copied for the both redexes, lest substitution in either redex should affect the other one. In doing so, graph reduction also copies the redex ((λv. v) w), thereby duplicating work.

Optimal evaluation (in Lévy's sense 4 5) is a technique of reducing lambda terms to their normal forms, in practice done through so-called interaction nets, which are graphs of special symbols & unconditionally local rewriting rules. To reduce a lambda term, an optimal evaluator (1) translates the term to an interaction net, (2) applies a number of interactions (rewritings) in an implementation-defined order, & (3) when no more rules can be applied, translates the resulting net back to the syntactical universe of the lambda calculus. Unlike the other discussed techniques, it performes no copying whatsoever, thereby achieving maximal sharing of redexes.

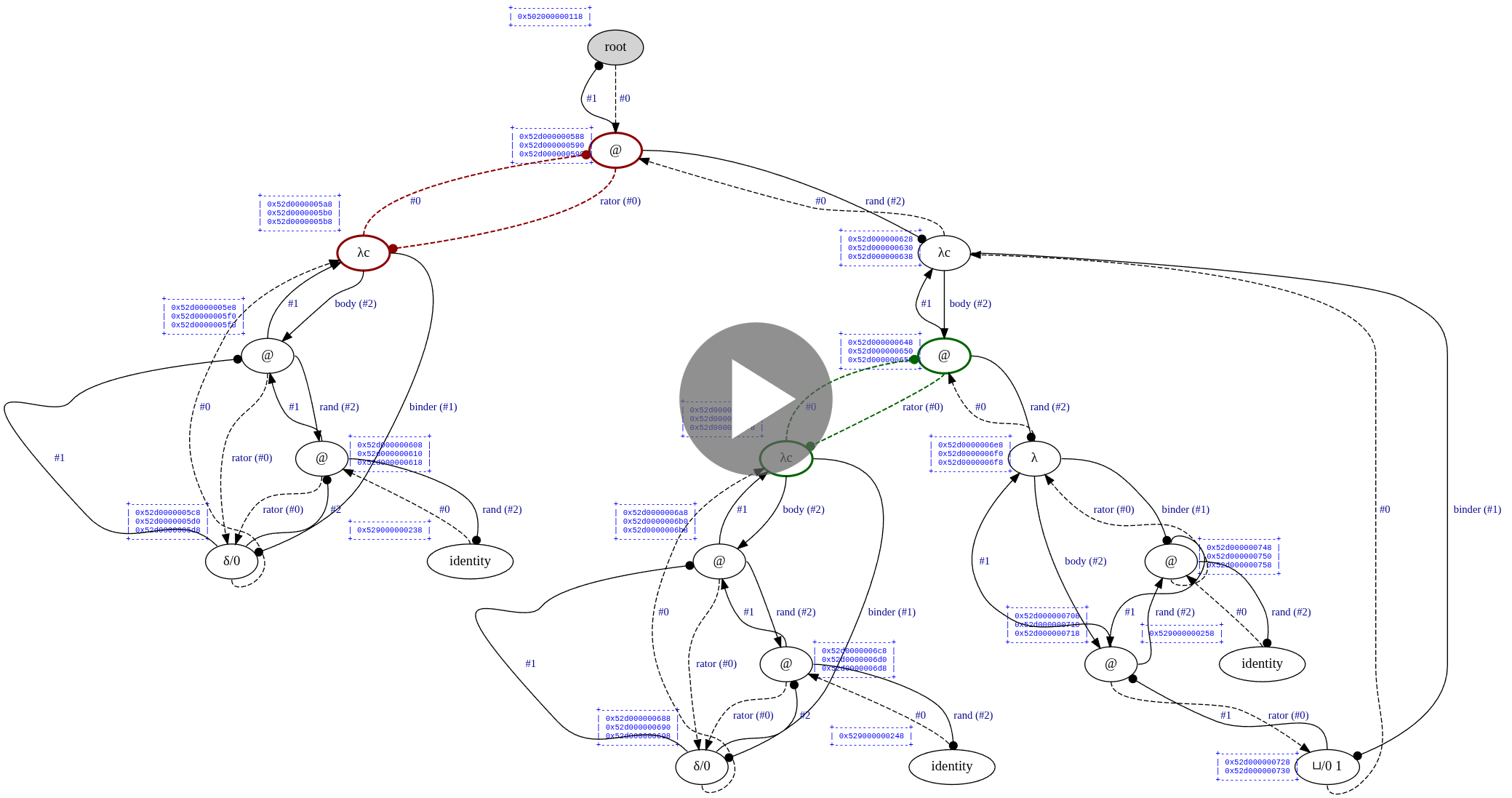

In practice, this is how the complete reduction of Church numeral 2^2 looks like:

(Green nodes are "active" nodes, i.e., those that interact with each other.)

Each edge has its own symbol: one of @, λ, ◉, ▽/i, ⌒/i, or S (which appears later during read-back), where i is an unsigned "index" that can change during interaction. The first two symbols, @ & λ, have the expected meaning; the other symbols are used for bookkeeping work. Among those, the most important one is ▽/i, which shares a single piece of a graph between two other edges. Sharing edges can be nested arbitrarily deep, allowing for sharing of an arbitrary number of redexes.

For an evaluator to be optimal, it must satisfie the following properties:

- The normal form, if it exists, is alwaies reached.

- The normal form, if it exists, is reached in a minimum number of beta reductions.

- Redexes of the same origin are shared & reduced in a single step.

- No unneeded redexes are ever reduced.

Optiscope operates in five discrete phases: (1) weak reduction, (2) full reduction, (3) unwinding, (4) scope removal, & (5) loop cutting. The first two phases performe interaction net reduction; the latter phases read back the reduced net into a net that can be directly interpreted as a lambda calculus expression. Weak reduction achieves true Lévy-optimality by reducing onely needed redexes (i.e., neither duplicating work nor touching redexes whose result will be discarded); the latter phases are to be understood as "extensions" that are not formally Lévy-optimal. In particular, although full reduction is guaranteed to reach beta normal forms, it is allowed to fire redexes whose result will be eventually discarded by subsequent computation. This choice is made of practical concerns, since implementing full Lévy-optimal reduction is neither easy, nor necessary; all functional machines in practice are weak anywaies.

Mathematically, our implementation follows the Lambdascope formalisme 1, which is perhaps the simplest (among many others) proposal to optimality, involving onely six types of nodes & three rule schemes. As here we make no attempt at giving optimality a formal treatment, an interested reader is invited to read the paper for more details & aske any related questions in the issues.

Consider the following example from examples/lamping-example.c:

#include "../optiscope.h"

static struct lambda_term *

lamping_example(void) {

struct lambda_term *g, *x, *h, *f, *z, *w, *y;

return apply(

lambda(g, apply(var(g), apply(var(g), lambda(x, var(x))))),

lambda(

h,

apply(

lambda(f, apply(var(f), apply(var(f), lambda(z, var(z))))),

lambda(w, apply(var(h), apply(var(w), lambda(y, var(y))))))));

}

int

main(void) {

optiscope_open_pools();

optiscope_algorithm(stdout, lamping_example());

puts("");

optiscope_close_pools();

}This is the exact encoding of the following example from the optimality section:

((λg. (g (g (λx. x))))

(λh. ((λf. (f (f (λz. z))))

(λw. (h (w (λy. y)))))))

By typing ./command/example lamping-example from the root directory, we can see the output:

$ ./command/example.sh lamping-example

(λ 0)

The whole term evaluates to the identity lambda, as expected.

In Optiscope, it is possible to observe all the interaction steps involved in computing the finall result. However, since there are so many interactions involved in this example, we will onely focus on the first ten & the last ten ones. In order to aske Optiscope to draw an SVG file after each interaction, insert the following lines into optiscope.h:

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_TRACING

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_STEP_BY_STEP

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_GRAPHVIZThe visualization will then be as follows:

In this section, we demonstrate how to achieve side effects & manual resource management in the interaction net framework.

Consider this program from examples/palindrome.c:

// Includes omitted...

static uint64_t

my_puts(const uint64_t s, const uint64_t token) {

(void)token;

return (uint64_t)puts((const char *)s);

}

static uint64_t

my_gets(const uint64_t token) {

(void)token;

char *const s = malloc(256);

if (NULL == s) { perror("malloc"), abort(); }

scanf("%255s", s);

return (uint64_t)s;

}

static uint64_t

my_free(const uint64_t s, const uint64_t token) {

(void)token;

free((void *)s);

return 0;

}

static uint64_t

my_strcmp(const uint64_t s1, const uint64_t s2) {

return 0 == strcmp((const char *)s1, (const char *)s2) ? 1 : 0;

}

static uint64_t

is_palindrome(uint64_t s) {

const char *const chars = (const char *)s;

const size_t len = strlen(chars);

for (size_t i = 0; i < len / 2; i++) {

if (chars[i] != chars[len - 1 - i]) { return 0; }

}

return 1;

}

static struct lambda_term *

program(void) {

struct lambda_term *rec, *token, *s;

// clang-format off

return fix(lambda(rec, lambda(token, perform(

binary_call(my_puts,

cell((uint64_t)"Enter your palindrome or type 'quit':"), var(token)),

bind(s,

unary_call(my_gets, var(token)),

if_then_else(

binary_call(my_strcmp, var(s), cell((uint64_t)"quit")),

binary_call(my_free, var(s), var(token)),

perform(

if_then_else(

unary_call(is_palindrome, var(s)),

binary_call(my_puts,

cell((uint64_t)"This is a palindrome!"), var(token)),

binary_call(my_puts,

cell((uint64_t)"This isn't a palindrome."), var(token))),

perform(

binary_call(my_free, var(s), var(token)),

apply(var(rec), var(token))))))))));

// clang-format on

}

int

main(void) {

optiscope_open_pools();

optiscope_algorithm(NULL, apply(program(), cell(0)));

optiscope_close_pools();

}It executes as follows:

$ ./command/example.sh palindrome

Enter your palindrome or type 'quit':

level

This is a palindrome!

Enter your palindrome or type 'quit':

radar

This is a palindrome!

Enter your palindrome or type 'quit':

obfuscation

This isn't a palindrome.

Enter your palindrome or type 'quit':

quit

Without monads or effect handlers, we have just done some input/output interspersed with pure lazy computation!

Let us see how this example works step-by-step:

- We enclose the whole program in

fix, which is our built-in fixed-point combinator. Therecparameter stands for the current lambda function to be invoked recursively. - Next, we accept the parameter

token, which stands for an effect token. Its purpose will be clear later. - The first thing we doe in the function body is calling

my_puts. Here,my_putsis an ordinary C function that acceptss, the string to be printed, &token. By callingperform, we force the evaluation ofmy_putsto be performed right now. - We bind the call of

my_getsto the variables. Here, the execution ofmy_getswill also be forced due tobind; the rest of the code will deal with already evaluateds. - We proceed with calling

my_strcmp. If the string is"quit", we manually callmy_free& finish the evaluation. We doe not need to forcemy_freehere, because it appears in a tail call position. - If the input string is not

"quit", we force the evaluation ofis_palindromewith its both (side-effectfull) branches. - We finally force

my_freeto ensure no memory leaks occur, & proceed with a recursive call.

From the optimality section, you remember that optimal reduction shares all explicit & virtual redexes -- if they are constructed "in the same way". This is the exact reason why we need to passe the token parameter to every side-effectfull function: we trick Optiscope to make it think that, given that the side-effecting redexes are constructed differently, it must repeatedly re-evaluate them each time it focuses on them; otherwise, it would just "cache" their results, once they are executed for the first time. Since the reduction strategy is fixed, it is safe to rely on Optiscope performing side effects in the exact order we wrote them.

Finally, notice that my_strcmp & is_palindrome are both pure functions used as mere program subroutines. In fact, we use pure native functions quite extensively in tests.c, which allowed us to test Optiscope on a variety of classical algorithms, such as functional quicksort & the Ackermann function. Naturally, this opens another path for investigation: what if we delegate CPU-bound computation to native functions & aske the optimal machine to efficiently share those computations?

In this section, we give well-formednesse rules for side-effectfull computations in Optiscope.

We take our inspiration from the use of monads in call-by-need functional programming languages, such as Haskell. The intuition is as follows: whenever we would write _ <- action; k in Haskell, we write perform(action, k) in Optiscope; whenever we would write x <- comp; k in Haskell, we write bind(x, action, k) in Optiscope; whenever we would end execution with action in Haskell (e.g., putStrLn "goodbye" at the end of do-notation), we doe the same in Optiscope.

We write comp/pure for pure computations, i.e., those not conteyning bind or perform, & comp/impure for computations involving side effects. The formal rules for impure computations are as follows:

- If

fis a side-effectfull function, thenunary_call(f, token)/impure, wheretokenis a cell passed downwards. - If

fis a side-effectfull function &rand/impure, thenbinary_call(f, rand, token)/impure, wheretokenis a cell passed downwards. - If

action/impure&k/impure, thenperform(action, k)/impure. - If

action/impure&k/impure, thenbind(x, action, k)/impure. - If

action/impure&if_then/impure&if_else/impure, thenif_then_else(action, if_then, if_else)/impure. - If

comp/pure, thencomp/impure.

The onely difference between Optiscope and Haskell-style monads is that, while monads are first-class citizens in Haskell, they merely manifest themselves as well-formednesse rules in Optiscope. While the Haskell approach allows for more flexibility & preserves the conceptual purity of I/O functions, it requires the I/O monad to be incarnated into the language & to be treated specially by the runtime system; on the other hand, the Optiscope approach onely requires carefull positioning of effectfull computation, which can be easily achieved through a superimposed type system that implements the rules above.

Which approach is better is a topic of further discussion. However, the point of Optiscope is to merely show that unrestricted, user-provided side effects are perfectly expressible within interaction nets & optimal reduction.

Another interesting example, although perhaps not that practical, is to execute an optimal machine from within an optimal machine:

Show the example

// Includes omitted...

static uint64_t is_zero(const uint64_t x) { return 0 == x; }

static uint64_t minus_one(const uint64_t x) { return x - 1; }

static uint64_t add(const uint64_t x, const uint64_t y)

{ return x + y; }

static uint64_t multiply(const uint64_t x, const uint64_t y)

{ return x * y; }

// `scott_nil`, `scott_cons`, & `scott_list_1_2_3_4_5`.

static struct lambda_term *

fix_factorial_function(void) {

struct lambda_term *f, *n;

return lambda(

f,

lambda(

n,

if_then_else(

unary_call(is_zero, var(n)),

cell(1),

binary_call(

multiply,

var(n),

apply(var(f), unary_call(minus_one, var(n)))))));

}

static uint64_t optiscope_inside_optiscope_result = 0;

static uint64_t

extract_result(const uint64_t n) {

optiscope_inside_optiscope_result = n;

return 0;

}

static uint64_t

inner_factorial(const uint64_t n) {

struct lambda_term *const term = unary_call(

extract_result, apply(fix(fix_factorial_function()), cell(n)));

optiscope_algorithm(NULL, term);

return optiscope_inside_optiscope_result;

}

static struct lambda_term *

scott_factorial_sum(void) {

struct lambda_term *rec, *list, *x, *xs;

return fix(lambda(

rec,

lambda(

list,

apply(

apply(var(list), cell(0)),

lambda(

x,

lambda(

xs,

binary_call(

add,

unary_call(inner_factorial, var(x)),

apply(var(rec), var(xs)))))))));

}

static struct lambda_term *

optiscope_inside_optiscope(void) {

return apply(scott_factorial_sum(), scott_list_1_2_3_4_5());

}Let us break down this example step-by-step:

- The

fix_factorial_functionfunction merely computes the factorial ofnusing recursion & native cells. - The

inner_factorialfunction accepts an integern& tells Optiscope to computefix_factorial_functionon thisn. When the computation is complete, we extract the result withextract_resultinto a global variable. - Next, the

scott_factorial_sumfunction computes a factorial sum of a Scott-encoded list. However, instead of directly computing the factorial, we callinner_factorial, thereby delegating the work to a lower-level optimal machine. - Finally,

optiscope_inside_optiscopelaunches the algorithm on a Scott list[1, 2, 3, 4, 5], eventually obteyning the resultcell[153], as evidenced in the tests.

That is, user-provided functions are given the right to performe all the variety of things, including running Optiscope itself! Moreover, as the memory pools are global to the whole program, the high-level & low-level optimal machines share the same memory regions during execution. Whether this technique has practical applications is a topic of future research.

Optimal XOR efficient? I made a fairly non-trivial effort at optimizing the implementation, including leveraging compiler- & platform-specific functionality, yet, our benchmarks revealed that optimal reduction à la Lambdascope performes many times worse than a traditional environment machine written in Haskell; for instance, whereas Optiscope needs some 8 seconds to sort & sum up a Scott-encoded list of onely 500 elements (in decreasing order), the Haskell implementation handles 5000 elements in just 4 seconds. On 1000 elements, Optiscope worked for ~1 minute 10 seconds. In general, the nature of performance penalty caused by optimal reduction is unclear; however, with increasing list sizes, the factor by which Optiscope runs slower is onely increasing.

Similar stories can be told about the other benchmarks. At one moment, I wondered if I merely implemented Lambdascope incorrectly because of this excerpt from the paper:

A prototype implementation, which we have dubbed _lambdascope_, shows that

out-of-the-box, our calculus performs as well as the _optimized_ version of the

reference optimal higher-order machine BOHM (see [2]) (hence outperforms the

standard implementations of functional programming languages on the same

examples as BOHM does).

This is a very interesting excerpt, because while it is concerned with efficiency, it says nothing in particular about it, save that their implementation is as fast as BOHM. So the question is: how fast is BOHM?

I downloaded BOHM1.1 & wrote the following Scott insertion sort benchmark for 1000 elements:

Show

def scottNil = \f.\g.g;;

def scottCons = \a.\b.\f.\g.(f a b);;

def scottSingleton = \x.(scottCons x scottNil);;

def lessEqual = \x.\y.if x <= y then 1 else 0;;

def scottInsert = rec scottInsert = \elem.\list.

let onNil = (scottSingleton elem) in

let onCons = \h.\t.

if (lessEqual elem h) == 1

then (scottCons elem (scottCons h t))

else (scottCons h (scottInsert elem t)) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def scottInsertionSort = rec scottInsertionSort = \list.

let onNil = scottNil in

let onCons = \h.\t.(scottInsert h (scottInsertionSort t)) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def scottSumList = rec scottSumList = \list.

let onNil = 0 in

let onCons = \h.\t.h + (scottSumList t) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def generateList = rec generateList = \n.

if n == 0

then scottNil

else (scottCons (n-1) (generateList (n-1)));;

def benchmarkTerm =

(scottSumList (scottInsertionSort (generateList 1000)));;

benchmarkTerm;;

Then I typed #load "scott-insertion-sort.bohm";; and... it hanged my computer.

For 150 elements, it executed almost instantly, but it was still of no rival to Haskell & OCaml.

Also read the following excerpt from 3, section 12.4:

BOHM works perfectly well for pure λ-calculus: much better, in average, than all

"traditional" implementations. For instance, in many typical situations we have

a polynomial cost of reduction against an exponential one.

Interesting. What are these "typical situations"? In section 9.5, the authors provide detailed results for a few benchmarks: Church-numeral factorial, Church-numeral Fibonacci sequence, & finally two Church-numeral terms λn.(n 2 I I) & λn.(n 2 2 I I). On the two latter ones, Caml Light & Haskell exploded on larger values of n, while BOHM was able to handle them.

Next:

Unfortunately, this is not true for "real world" functional programs. In this

case, BOHM's performance is about one order of magnitude worse than typical

call-by-value implementations (such as SML or Caml-light) and even slightly (but

not dramatically) worse than lazy implementations such as Haskell.

Looking at my benchmarks, I cannot call it "slightly worse", but rather "dramatically worse". The authors doe not elaborate what real-world programs they tested BOHM on, except for a quicksort algorithm from section 12.3.2 & the append function from section 12.4.1, for which they doe not provide comparison benchmarks with traditional implementations.

Finally, the authors conclude:

The main reason of this fact should be clear: we hardly use truly higher-order

_functionals_ in functional programming. Higher-order types are just used to

ensure a certain degree of parametricity and polymorphism in the programs, but

we never really consider functions as _data_, that is, as the real object of the

computation -- this makes a crucial difference with the pure λ-calculus, where

all data are eventually represented as functions.

Well, in our benchmarks, we represent all data besides primitive integers as functions. Nonethelesse, BOHM was still much slower than our 50-line evaluators in Haskell & OCaml.

What conclusions should we draw from this? Have Haskell & OCaml so advanced in efficiency over the decades? Or does BOHM demonstrate superior performance on Churh numerals onely? Should we invest our time in making optimality efficient, given that simpler, unoptimized approaches prove to be more performant? I have no definite answer to these questions, but the point is: Optiscope is onely meant to incorporate native function calls into optimal reduction, & it is by no means to be understood as a reduction machine aimed at maximum efficiency. While it is true that Optiscope is a heavily optimized implementation of Lambdascope, this fact does not entail that it is immediately faster than more traditional approaches. For now, if you want to develop a high-performance call-by-need functional machine, it is presumably better to take the well-known Spinelesse Taglesse G-machine 6 as a starting point.

Now, there are two possible avenues to mitigate the performance issue. The first one: since interaction nets provide a natural means for parallelization (sometimes termed microscopic parallelisme), it is possible to distribute interactions across many CPU/GPU cores, or even utilize a whole computing cluster. The second one: it should be possible to apply a supercompilation passe before optimal reduction, to make it statically remove administrative annihilation/commutation interactions that plague most of the computation. (For a five-minute introduction to supercompilation, see Mazeppa's README.) Of course, it is possible to mix both of the approaches, in which case optimal reduction might indeed become a strong competitor to traditional reduction methods.

-

Node layout. We interpret each graph node as an array

aofuint64_tvalues. At positiona[-1], we store the node symbol; ata[0], we store the principal port; at positions froma[1]toa[3](inclusively), we store the auxiliary ports; at positions starting froma[4], we store additional data elements, such as function pointers or computed cell values. The number of auxiliary ports & additional data elements determines the total size of the array: for erasers, the size in bytes is2 * sizeof(uint64_t), as they need one position for the symbol & another one for the principal port; for applicators & lambdas having two auxiliary ports, the size is3 * sizeof(uint64_t); for unary function calls, the size is4 * sizeof(uint64_t), as they have one symbol, two auxiliary ports, & one function pointer. Similar calculation can be done for all the other node types. -

Symbol layout. The difficulty of representing node symbols is that they may or may not have indices. Therefore, we employ the following scheme:

0is the root symbol,1is an applicator,2is a lambda,3is an eraser,4is a scope (which appears onely during read-back), & so on until value15, inclusively; now the next9223372036854775800values are occupied by duplicators, & the same number of values is then occupied by delimiters. Together, all symbols occupy the full range ofuint64_t; the indices of duplicator & delimiter symbols can be determined by proper subtraction. -

Port layout. Modern x86-64 CPUs utilize the 48-bit addresse space, leaving 16 highermost bits unused (i.e., sign-extended). We therefore utilize the highermost 2 bits for the port offset (relative to the principal port), & then 4 bits for the algorithm phase, which is either

PHASE_REDUCE_WEAKLY,PHASE_REDUCE_FULLY,PHASE_REDUCE_FULLY_AUX,PHASE_UNWIND,PHASE_SCOPE_REMOVE,PHASE_LOOP_CUT,PHASE_GC,PHASE_GC_AUX, orPHASE_STACK. The following bits constitute a (sign-extended) addresse of the port to which the current port is connected to. This layout is particularly space- & time-efficient: given any port addresse, we can retrieve the principal port & from there goe to any neighbouring node in constant time; with mutable phases, we avoid the need for history lookups during graph traversals. (The phase value is onely encoded in the principal port; all consequent ports have their phases zeroed out.) The onely drawback of this approach is that ports need to be encoded when being assigned & decoded upon use. -

O(1) memory management. We have implemented a custom pool allocator that has constant-time asymptotics for allocation & deallocation. For each node type, we have a separate global pool instance to avoid memory fragmentation. On Linux, these pools allocate 2MB huge pages that lessen frequent TLB misses, to account for cases when many nodes are to be manipulated; if either huge pages are not supported or Optiscope is running on a non-Linux system, we default to

malloc.

- Weak reduction. In real situations, the result of pure lazy computation is expected to be either a constant value or a top-level constructor. Even when one seeks reduction under binders & other constructors, one usually also wants controlling definition unfoldings or reusing already performed unfoldings 7 to keep resulting terms manageable. We therefore adopt BOHM-style weak reduction 8 as the initiall, most important phase of our algorithm. Weak reduction repeatedly reduces the leftmost outermost interaction until a constructor node (i.e., either a lambda abstraction or cell value) is connected to the root, reaching an interface normal form. This phase directly implements Lévy-optimal reduction by performing onely needed work, i.e., avoiding to work on an interaction whose result will be discarded later.

(A shocking side note: per section "5.6 Optimal derivations" of 3, a truely optimal machine must necessarily be sequential, because otherwise, the machine risks at working on unneeded interactions!)

-

Garbage collection. Specific types of interactions may cause whole subgraphs to be fully or partially disconnected from the root, such as when a lambda application rejects its operand or when an if-then-else node selects the correct branch, rejecting the other one. In order to battle memory leaks during weak reduction, we implement eraser-passing garbage collection described as follows. When our algorithm determines that the most recent interaction has rejected one of its connections, our garbage collector commences incremental propagation of erasers by connecting a newly spawned eraser to the rejected port; iteratively, garbage collection at a specific port necessarily results in either freeing the node in question & continuing the propagation to its immediate neighbours or leaving the eraser connection untouched, when the former operation cannot be carried out safely. (However, we doe also eliminate some uselesse duplicator-eraser combinations as discussed in the paper, which has a slightly different semantics.)

Our rules are inspired by Lamping's algorithm 2 / BOHM 8: although perfectly local, constant-time graph operations, they doe not count as interaction rules, since garbage collection can easily happen at any port, including non-principal ones.- We onely execute garbage collection during weak reduction. For the later algorithmic phases, garbage collection does not provide considerable benefit with our current implementation.

-

Sharing elimination. When the argument of the application turnes out to be an atomic node, we eagerly eliminate the sharing structure of the lambda function being applied to; that is, we simply clone the atomic node into all the places where it is expected to be substituted. The reasoning behind this strategy is to reduce the overall graph size by eliminating unnecessary sharing, inasmuch as there is no point of sharing that bears neither actuall computation, nor potentiall computation. Currently, atomic nodes are defined to be erasers, cells, identities, & references, i.e., nodes that are trivially cloneable in our implementation.

-

Multifocusing. We have implemented a special dynamic array (the "multifocus") in which we record active nodes, i.e., nodes ready to participate in an interaction. We maintaine a number of multifocuses for each interaction type, which together comprise the global "context" of x-rules normalization. During full reduction & read-back, we implement normalization as follows: (1) we traverse the whole graph to populate the aforementioned set of multifocuses with active nodes; (2) if we have found none, terminate the algorithm; (3) otherwise, we iteratively fire interactions in these multifocuses until their exhaustion; (4) returne back to step (1).

- We may also use multifocuses for other purposes, because they naturally behave like a stack. Currently, we use one multifocus for garbage collection, one for eager unsharing, & another one for the weak reduction stack.

-

Special lambdas. We divide lambda abstractions into four distinct categories: (1)

SYMBOL_GC_LAMBDA, lambdas with no parameter usage, called garbage-collecting lambdas; (2)SYMBOL_LAMBDA, lambdas with at least one parameter usage, called relevant lambdas; (3)SYMBOL_LAMBDA_C, relevant lambdas without free variables; & finally (4)SYMBOL_IDENTITY_LAMBDA, identity lambdas. Although onely one category is sufficient to expresse all of computation, we employ this distinction for optimization purposes: if we know the lambda category at run-time, we can implement the reduction more efficiently. For instance, instantiating an identity lambda boils down to simply connecting the argument to the root port, without spawning more delimiters; likewise, commutation of a delimiter node withSYMBOL_LAMBDA_Cboils down to simply removing the delimiter, as suggested in section 8.1 of the paper. -

Delimiter compression. When the machine detects a sequence of chained delimiters of the same index, it compresses the sequence into a single delimiter node endowed with the number of compressed nodes; afterwards, this new node behaves just as the whole sequence of delimiters would, thereby requiring significantly lesse interactions. The machine performes this operation both statically & dynamically: statically during the translation of the input lambda term, dynamically during delimiter commutations. In the latter case, i.e., when the current delimiter commutes with another node of arbitrary type, the machine performes the commutaion & checks whether the commuted delimiter(s) can be merged with adjacent delimiters, if any. With this optimization, the oracle becomes dozens of times faster on some benchmarks & uncomparably faster on others (e.g.,

benchmarks/scott-quicksort.c).- For simplicity, delimiter compression is performed onely during weak reduction. Once weak reduction is complete, we explicitly traverse the graph to unfold all delimiters into sequences.

- C.f. run-length encoding.

-

References. Following HVM's terminology, a reference is a special node that lazily expands to a lambda term, which is then translated to a corresponding net in a single interaction. Strictly speaking, references doe not contribute to the expressivenesse of the system, but they tend to be farre more efficient than our (optimal!) fixed-point operator. In addition to improved efficiency, references naturally support mutual recursion, because every Optiscope reference corresponds to a C function taking zero parameters & returning a lambda term. In the benchmarks, we prefer to implement recursion on the basis of references.

-

Graphviz intergration. Debugging interaction nets is a particularly painfull exercise. Isolated interactions make very little sense, yet, the cumulative effect is somehow analogous to conventional reduction. To simplifie the challenge a bit, we have integrated Graphviz (in debug mode onely) to display the whole graph between consecutive algorithmic phases, & also before each interaction, if requested. Alongside each node, our visualization also displays an ASCII table of port addresses, which has proven to be extremely helpfull in debugging various memory management issues in the past. (Previously, in addition to visualizing the graph itself, we used to have the option to display blue-coloured "clusters" of nodes that originated from the same interaction (either commutation or Beta); however, it was viable onely for small graphs, & onely as long as computation did not goe too farre.)

- Despite that interaction nets allow for a huge amount of parallelisme, Optiscope is an unpretentiously sequential reducer. We doe not plan to make it parallel, perhaps except for (unordered) full reduction.

performcalls can onely be executed during weak reduction, inasmuch as the later phases doe not guarantee the order of reduction. In case aperformcall is detected after weak reduction is complete, a panic message will be emitted.- We doe not guarantee what will happen with ill-formed terms, such as when an if-then-else expression accepts a lambda as a condition. In general, we simply decide to commute such agents, but the overall result can be hard to predict.

- Optiscope cannot detect when two syntactically idential configurations occur at run-time; that is, the avoidance of redex duplication is relative to the initiall term, not to the computational pattern exhibited by the term.

- On conventional problems, Optiscope is in fact many times slower than traditional implementations, wherefore it is more of an interesting experiment rather than a production-ready technology.

Thanks to Marvin Borner (@marvinborner) for usefull discussions about optimality & side effectfull computation, as well as revealing a crucial memory management bug when activating both active scopes.

- Asperti, Andrea, Cecilia Giovannetti, and Andrea Naletto. "The Bologna optimal higher-order machine." Journal of Functional Programming 6.6 (1996): 763-810.

- Lafont, Yves. "Interaction combinators." information and computation 137.1 (1997): 69-101.

- Mackie, Ian. "YALE: Yet another lambda evaluator based on interaction nets." Proceedings of the third ACM SIGPLAN international conference on Functional programming. 1998.

- Pedicini, Marco, and Francesco Quaglia. "A parallel implementation for optimal lambda-calculus reduction." Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGPLAN international conference on Principles and practice of declarative programming. 2000.

- Pinto, Jorge Sousa. "Weak reduction and garbage collection in interaction nets." Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 86.4 (2003): 625-640.

- Mackie, Ian. "Efficient λ-evaluation with interaction nets." International Conference on Rewriting Techniques and Applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004.

- Mackie, Ian. "Encoding strategies in the lambda calculus with interaction nets." Symposium on Implementation and Application of Functional Languages. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005.

- van Oostrom, Vincent. "Explicit substitution for graphs." Nieuwsbrief van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Theoretische Informatica 9 (2005): 34-39.

- Hassan, Abubakar, Ian Mackie, and Shinya Sato. "Compilation of interaction nets." Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 253.4 (2009): 73-90.

- Hassan, Abubakar, Ian Mackie, and Shinya Sato. "An implementation model for interaction nets." arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.07164 (2015).

For readers unfamiliar with interaction nets, we recommend the originall Lafont's paper:

- Lafont, Yves. "Interaction nets." Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages. 1989.

A more comprehensive collection of interaction net research can be found in @marvinborner's interaction-net-resources.

Optiscope is aimed at being as correct as possible, with regards to the Lambdascope specification & the general understanding of the lambda calculus. To back up this endeavor financially, any person to discover a semantic bug will get a $1000 bounty in Bitcoin. A semantic bug constitutes a situation when some input lambda term is either reduced to an incorrect result, or the algorithm does not terminate. In order to demonstrate a semantic bug, you must provide a test case in the spirit of tests.c & show how your term would reduce normally. (Non-termination bugs are the trickiest, because it might be unclear if the machine is just inefficient or it is falling in a cycle. In order to prove your case, it might be necessary to pinpoint the cause of non-termination, instead of merely the fact of it.)

In addition to semantic bugs, there are various memory management issues that plague programs written in C. For any such issue, a reporter will get a $100 bounty in Bitcoin. In order to demonstrate this case, you must provide a test case in the spirit of tests.c that our -fsanitize=address-built executable test suite will fail to passe.

In order to report either type of a bug, kindly open an issue in this repository. If your case meets the eligibility criteria, I will aske for your email addresse & reach out to you as soon as possible. In case of any ambiguity, I will use my best judgement.

Semantic bugs related to extra functionality like native function calls & if-then-else nodes are not eligible for bounty, as they exist outside the realm of the pure lambda calculus.

Footnotes

-

van Oostrom, Vincent, Kees-Jan van de Looij, and Marijn Zwitserlood. "Lambdascope: another optimal implementation of the lambda-calculus." Workshop on Algebra and Logic on Programming Systems (ALPS). 2004. ↩ ↩2

-

Lamping, John. "An algorithm for optimal lambda calculus reduction." Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages. 1989. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Asperti, Andrea, and Stefano Guerrini. The optimal implementation of functional programming languages. Vol. 45. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Lévy, Jean-Jacques. Réductions correctes et optimales dans le lambda-calcul. Diss. Éditeur inconnu, 1978. ↩

-

Lévy, J-J. "Optimal reductions in the lambda calculus." To HB Curry: Essays on Combinatory Logic, Lambda Coalculus and Formalism (1980): 159-191. ↩

-

Jones, Simon L. Peyton. "Implementing lazy functional languages on stock hardware: the Spineless Tagless G-machine Version 2.5." (1993). ↩

-

Jonsson, Peter A., and Johan Nordlander. "Taming code explosion in supercompilation." Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGPLAN workshop on Partial evaluation and program manipulation. 2011. ↩

-

Asperti, Andrea, Cecilia Giovannetti, and Andrea Naletto. "The Bologna optimal higher-order machine." Journal of Functional Programming 6.6 (1996): 763-810. ↩ ↩2